A Visual Way to Learn Numbers Without Counting Gains Popularity

“Although most children learn to read at least three or four when they go to kindergarten, there are children who do not have the opportunity, and those children are in a really big problem in kindergarten,” said Art Baroody, professor. from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who spent his career studying the best ways to teach counting, numbers and arithmetic concepts to young children. “The reason for that humility involves building an understanding of what a person is, what is two, what is three, what is four, which is the basis of the concept of number. There is a lot to build on that understanding.”

As children get older, subitizing can become more complex and useful for understanding more advanced math concepts. Consider a set of seven dots like this:

Most people can’t identify many of these dots, especially if they’re not arranged in a regular pattern, but they can recognize small groups. Others may see two groups of three and an additional dot. Others can see a group of four and a group of three. There are many possibilities.

Doug Clements and Julie Sarama, a research team at the University of Denver, call this rapid categorization “conceptual subitizing.” They say it helps children name and decompose numbers, which is useful for learning addition and subtraction facts. For example, 7 + 5 can be a tricky sum to learn. But a child who can’t subdivide may quickly see that 7 can be divided into 5 and 2. That makes it easy to add both 5s to make 10 and 2 more to make 12. “That makes sense and don’t forget it. ,” said Clements.

Counting from 7, of course, is another way. But it can be confusing to keep track of the other five as the child counts from 7 to 12. Children who can only add by counting quickly realize that they don’t have time to count when they are given a long addition worksheet. These children often resort to memorizing a series of meaningless numbers (5, 7, 12) which they quickly forget. “They skipped the step of making it meaningful,” Clements said. “In first grade, teachers will say, ‘You knew it last week.’ Now he has forgotten it.’ Well, he really didn’t know.”

Subiting seems to help with all kinds of math concepts, according to its proponents. In 2014, another group of researchers explained that third graders who can quickly group sets of small numbers, such as groups of three to two, have a more complex understanding of multiplication and can multiply faster. Some say that the ability to divide a number into smaller pieces that can be easily added builds an understanding of the relationship between part and whole and resources through fractions.

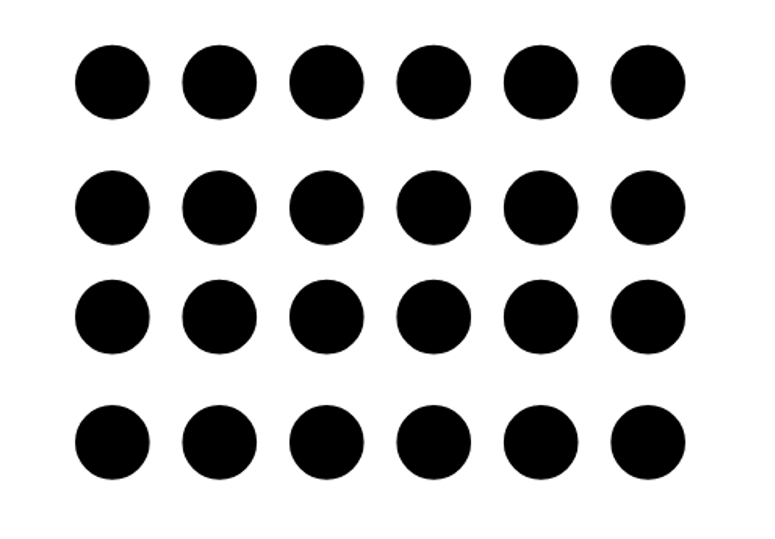

Clements and Sarama recommend using subitizing exercises at the end of elementary school. For example, a 24-dot list can reinforce the understanding of the concept of multiplication in grades three through five.

“Submissiveness is not something you get from a child,” Clements said. “You just keep developing it along with all the other skills you develop.”

Well, sometimes it’s childish things. Some researchers believe that five- or six-month-old infants pick up smaller numbers, such as twos and threes. That belief is based on a study in which infants gazed for longer periods of time due to price changes. As children grow, they begin to map number words to sets of objects, for example, “two socks,” and by age 2, most children can enter three objects, and 4- and 5-year-olds can substitute. up to five things.

Researchers have shown that increasing this innate ability can help children develop number sense. A study of two students who struggled with math, published in 2009, found that substitution helped. Baroody of the University of Illinois advocated the practice of teaching under the 2013 practice guide “Teaching Mathematics to Young Children,” of the Institute of Education Sciences, a research arm of the US Department of Education.

Several studies have shown that children with strong subitizing skills also tend to do better in math. For example, a 2022 study of more than 3,600 preschoolers in one southwestern school district found that children who were better subitizers also had better arithmetic skills in first grade. A 2020 study of 80 young children, ages 2 to 5, found that children who were able to tap into the number four, and who were taught to count, could usually answer the question “How many?” But the children who managed to enter only the third place showed only a partial understanding of the value.

However, the strong correlation between subitizing ability and math ability is not evidence that students will benefit from changing instruction. It is possible that powerful subitizers come from wealthy families who play a lot of board games. These high-income children also benefit from many other factors at home, from better nutrition to less stress, which may be driving their success in math.

Strong evidence that it’s worth investing classroom time in putting together small things, at least so far. In a new, but small study, 14 preschoolers ages 3 to 5 were randomly assigned to two different math interventions. Those who were given more practice in subitizing performed better on the cognitive test. The study, available online, is scheduled to be published in the December 2024 issue of the Journal of Mathematical Behavior. More and larger studies are needed.

Even without that evidence, many elementary school teachers have been incorporating reduction elements, sometimes called “quick pictures,” into their classrooms for decades. But structured teaching of the practice seems to be growing in popularity, based on conversations I’ve had with teachers, researchers and the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, a professional organization. Another motivation is the desire to tackle the huge achievement gap between rich and poor children by building a strong math foundation during the early years. Subitizing is clearly included in the Illinois math standards for preschoolers, while many other states suggest subitizing as an example of one way to teach numbers. Curriculum publishers are increasingly printing dot graphics to include in their materials.

Beth MacDonald, an associate professor of early childhood mathematics education at Illinois State University, said substitution was a hot topic at the International Conference on Mathematics Education earlier this summer. “People come and say, ‘Oh, we want to test this,’ ” said MacDonald, who wrote his book on rewriting a decade ago and is the author of several articles and studies I read to write this piece.

Although subiting is easy to do, experts say that sometimes they see it being taught incorrectly. One common mistake is asking students to count the dots. Researchers say that undermines a child’s self-confidence and ability to form mental images of sets.

Speed is important. Usually the dots are shown for a very long time, long enough for children to count them. “That’s a big mistake,” said Clement’s colleague Sarama, who explained to me that the brevity causes the children to imagine the picture on their own.

Sarama says that each dot task can be completed in 10 seconds for a total of three minutes a day. Value memory is formed, according to researchers, through brief but repeated exposure.

According to Milwaukee math coach Robinson, kids want to talk so much about all the different ways that they see the dots that it’s hard for teachers to move on to the next task. Children really enjoy subitizing.

And many children learn to cook at home. Researchers say the practice does not require fancy equipment and parents do not need to create dot cards. They advise parents to talk about values during daily activities. When you fold laundry, talk about matching pairs of socks. Or at the end of lunch, ask who will eat the three french fries left on the plate. Sometimes, you don’t need to count!